Uncertain Health in

an Insecure World – 99

“Fecal Matters”

Humans are made up of 50% somatic cells and 50% microbes!

Long before next-generation gene sequencing (NGS) technology,

using a simple little device (the compound microscope), Dutchman Antonie van

Leewenhoek (1632-1723; below) showed that the body’s oral and fecal bacterial

populations were very different.

Van Leewenhoek, the “father of microbiology”, also proved that the microbial flora he

called ‘animalcules’ (below) differed between

healthy and diseased humans.

The insight that healthy humans coexist with bacteria and

other bugs in a “microbiota” won

Joshua Lederberg (1925-2008; below) the 1958 Nobel

Prize for Medicine & Physiology. Lederberg and his colleagues showed

that bacteria can mate and exchange genes (i.e., bacterial conjunction).

At

just 33 years of age, the new Nobel Laureate went west to found the Department

of Genetics at Stanford University. In

the 1950’s he and Carl Sagan raised concerns about the biological effects of

space travel, advising NASA to

isolate returning astronauts and sterilize equipment to prevent extraterrestrial microbes

from contaminating to Earth. In the 1960’s he worked with Stanford Computer Science

Department chair, Edward Feigenbaum, to develop the first artificial

intelligence platform, DENDRAL (a

portmanteau of dendritic algorithm).

And in 2001, Dr. Lederberg coined the term “human microbiome.”

Since 2008, the U.S. National Institutes of Health Human Microbiome Project (HMP) has been

characterizing the distribution and genomics of the microbial communities found

at multiple body sites, to determine whether and how changes in the human microbiome impact health. In conjunction with other members of the international Human Microbiome Consortium, the

HMP used NGS to characterize 3,000 genomes from bacteria, viruses and protozoans (below).

These projects generated a human

metagenomic big data repository for comparing microbes to the human cells with

which they co-exist (below). The 5-year US$115M HMP has studied the sharing of common microbe-cell

metabolic pathways and the exchange of genomic material, in both healthy

symbiotic and disease-producing states.

In June 2016, the Obama Administration launched the

follow-on US$121M Microbiome Initiative.

Like the Precision Medicine Initiative

(PMI) and the Cancer Moonshot, it’s

unclear if this program will be part of the Obama legacy, or be euthanized by

the new Donald Trump Administration.

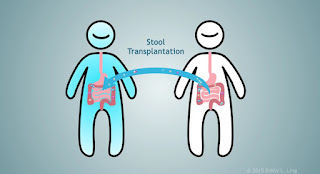

Fun Fact – the newest effective human transplant material is

feces.

Yes… you heard correctly!

Doctors can obtain fresh stool from healthy donors to

replenish the normal gut bacteria of patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile (C. diff.; above) infections. C. diff. toxin causes colonic

inflammation and chronic diarrhea. Annually, in the U.S. C. diff. infects between 640,000 and 820,000 Americans, killing

14,000. Fecal microbial transplant (FMT, a.k.a. “bacteriotherapy”) was shown to be more effective than oral vancomycin

therapy in preventing further infections in a study of 16 Dutch patients with

recurrent C. diff. colitis (New Eng. J. Med. 368: 407-415, 2013).

Not surprisingly, FMT patients have a preference for related donors.

Not surprisingly, FMT patients have a preference for related donors.

To address the problem of potentially lethal hospital-acquired C. diff. infections and the FMT “ick factor”, doctors at Canada’s Kingston General Hospital and the University of Western Ontario have now developed a 33 gut bacterial species of “pseudo-poo” that serves as a stool substitute, precluding the need for fecal material infusion. The lead doctors, Elaine Petrof and Gregory Gloor, like to think of the mixture a rectally administered yogurt! Microbial cocktails are now being tested in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD; Nature Biotechnology 33:787-788, 2015).

Investigators from the University

of Ottawa have reported significant differences in the metagenomics of gut

microbes in children with two genetically similar IBD's –

Crohn’s Disease and ulcerative colitis (UC). They have also shown that the

microbial dysbiosis of Crohn’s disease is associated with down-regulation of

mitochondrial proteins that detoxify H2S, and that Atopobium parvulum is the network

controller of other H2S-producing pro-inflammatory gut microbes (Nature Communications, 7: 13419, 2016).

In the last few years, recognition of the immunomodulatory

effects of the human microbiome has led start-ups and Big Pharma to seek out novel

therapies.

Boston-based Vendanta

Biosciences has been working on a “bug

drugs” since 2012, backed by private equity funds from PureTech Ventures. In 2015, they announced the successful

development of a 17 C. diff. strain called

VE202. This VE202 cocktail is thought to push out the bad C. diff. bugs by rejuvenating T-reg lymphocyte immune functions,

thereby reducing gut inflammation. In January 2015, the Janssen Biotech division of Johnson

& Johnson (JNJ) Pharmaceuticals licensed this novel technology from

Vendanta for an initial fee of US$241M. The Jansen Human Microbiome Institute (JHMI), established in Cambridge MA in

2014, is intensively plumbing microbiome therapeutics with numerous partners. The head of JNJ Innovation at the JHMI, Anuk Das (below), believes that this pipeline will be effective in autoimmune,

inflammatory and infectious diseases.

Seres Therapeutics (NASDAQ:MCRB) became the first company in the human microbiome sector to go public. Backed by Flagship Ventures, Seres began as a 2010 Cambridge MA start-up. Their June 2015 IPO netted US$139M ($18 per share), based on the promising results of phase-1 clinical trials with SER-109 (Nature Biotechnology 33: 787-788, 2015). SER-109 (ECOSPOR™) is a carefully controlled mix of 50 bacterial spores obtained from healthy donors. Although FDA-designated as a “breakthrough therapy,” in July 2016 Seres announced that SER-109 “unexpectedly” failed to meet its goal in a phase-2 clinical trial – it did not reduce the relative risk of C. diff. recurrence compared to placebo. Not unexpectedly, MCRB share prices tumbled 75% from $35.77 to $8.74 per share.

Seres Therapeutics (NASDAQ:MCRB) became the first company in the human microbiome sector to go public. Backed by Flagship Ventures, Seres began as a 2010 Cambridge MA start-up. Their June 2015 IPO netted US$139M ($18 per share), based on the promising results of phase-1 clinical trials with SER-109 (Nature Biotechnology 33: 787-788, 2015). SER-109 (ECOSPOR™) is a carefully controlled mix of 50 bacterial spores obtained from healthy donors. Although FDA-designated as a “breakthrough therapy,” in July 2016 Seres announced that SER-109 “unexpectedly” failed to meet its goal in a phase-2 clinical trial – it did not reduce the relative risk of C. diff. recurrence compared to placebo. Not unexpectedly, MCRB share prices tumbled 75% from $35.77 to $8.74 per share.

Of course, Seres has other drugs in the pipeline. For example, SER-262 is a synthetically-derived microbiome modifying agent for C. diff. infection now in phase-1b trials. Seres’ other EcobioticR drugs are entering phase-1b studies for treating patients with inflammatory diseases like Crohn’s, UC and non-insulin dependent type-2 diabetes.

Among the many emerging companies attracting Pharma and VC

attention in the human microbiome therapeutics space are Enterome, Second Genome,

EpiBiome and uBiome.

The World Health Organization reports 1.7 billion global cases

of diarrheal disease per year, with 760,000 deaths per year in children under

the age of 5 years. The primary associations of this potentially lethal illness

are malnutrition, poor sanitation and contaminated drinking water. While this

disease is far more of a global public health risk, Pharma and VC will follow

Sutton’s Law, focusing their funds on the developed world’s perceived needs for new

technologies and drugs for C. diff.,

UC or Crohn’s disease.

We in the Square don’t pooh-pooh these fast emerging human microbiome

innovations.

But we loudly lament a market reality that sees “the others” impatiently waiting for the constipated global diffusion of such benefits.