Uncertain Health in

an Insecure World – 92

“Leitmotif”

Life offers up subtle themes and catch phrases that connect

deeply to the human mind. When music powerfully evokes a particular person or

place, like the animal characters in Peter

and The Wolf (Sergei Prokofiev, 1936), it’s called leitmotif.

Leonard Cohen wrote of such evocation in his folk gospel

anthem, Hallelujah:

“Now I’ve heard there was a secret chord,

That David played, and it pleased the Lord…

Well, it goes like this, the fourth, the

fifth,

The minor fall, and the major lift,

Bono has called Hallelujah, “the most perfect song in the world.” But it didn’t become popular

until decades after it was written in 1984. The head of CBS Records called it “a disaster.” The Rolling Stone review of

the album, Various Positions, did not

even mention the song. Velvet Underground’s John Cale covered it beautifully in

his 1991 Cohen tribute album, and Jeff Buckley breathed life into it in 1994

three years before his death. But there was only a ripple of interest. It was

only when Rufus Wainwright resurfaced it in the 2001 Shrek movie soundtrack that public awareness grew.

University of California at

Berkeley engineers studied the structure of 1,300 songs to determine what

makes popular music move the human brain. Their ‘hook theory’ posits that certain

chord progressions are more pleasing to the ear. Many pop songs are written in the

easy to play keys of C or G – they are full of those common chords – so no

surprise there. Songs in the key of C (and its relative minor, A) are by far

the most frequent. F and G chord progressions are also very common (above), lending to

the common criticism of formulaic “four

chord pop songs” featuring C, A minor, F and G chords. Songs written in C major

(or I) are best wrapped up with G

major (or V) chords. That’s why the G

to C (or the V to I) chord resolution is so common in

popular music.

However, as pointed out by lead hook theorist, Dave Carlton (below left), some of the greatest pop songs eschew this convention, using the F chord (IV) before the C major (a IV to I chord progression) to great effect: Let It Be (The Beatles, 1970, above), Don’t Stop Believing (Journey, 1981), She Will be Loved (Maroon 5, 2002), I Need You Now (Lady Antebellum, 2009) and Edge of Glory (Lady Gaga, 2011).

However, as pointed out by lead hook theorist, Dave Carlton (below left), some of the greatest pop songs eschew this convention, using the F chord (IV) before the C major (a IV to I chord progression) to great effect: Let It Be (The Beatles, 1970, above), Don’t Stop Believing (Journey, 1981), She Will be Loved (Maroon 5, 2002), I Need You Now (Lady Antebellum, 2009) and Edge of Glory (Lady Gaga, 2011).

Carlton notes that classical musicians use different chord

progressions when composing. And even pop song writers with classical training

– like John Mayer (1998 Berklee School of Music graduate) in Who Says (2009) –

approach the composing craft differently. Philadelphia public radio WHYY Radio

Times host Marty Moss-Coane explored the musical success formulas behind the

classic pop songs of summer. In July 2014, she interviewed Ryan Mikayawa,

another UC Berkeley hook theorist (above right). Mikayawa noted that the unique chord

progressions in John Legend’s All of Me (2014), while reminiscent of some prior

hits, were neither plagiarized nor formulaic.

When visiting Montreal in July 2007 for The Police’s reunion tour

concert, Gordon Matthew Thomas Sumner (a.k.a. Sting, above) agreed to undergo a

functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) brain scan at McGill University’s

Montreal Neurological Institute. The lead MNI psychologist, Dr. Daniel Levitin,

asked him to listen to music during the fMRI, which showed that “pieces of music that you or I wouldn’t have

seen as similar, his brain saw as similar.”

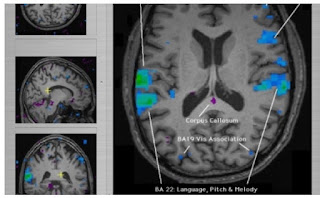

Sting’s brain triggered similar patterns (below) when listening to his Englishman in New York, and to The Rolling Stones’ (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction – both songs start with a low E on the bass. Again, when Sting listened to the Beatles 1960’s hit Girl and Astor Piazzolla’s composition Libertango – both in minor keys with an identical 3-note motif – his cerebellar fMRI activity was comparable.

Remarkably, normal non-musician volunteers’ brains did not make these subtle connections.

Sting’s brain triggered similar patterns (below) when listening to his Englishman in New York, and to The Rolling Stones’ (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction – both songs start with a low E on the bass. Again, when Sting listened to the Beatles 1960’s hit Girl and Astor Piazzolla’s composition Libertango – both in minor keys with an identical 3-note motif – his cerebellar fMRI activity was comparable.

Remarkably, normal non-musician volunteers’ brains did not make these subtle connections.

Can restoring normal brainwaves help to treat brain injury

and disease?

A line of research led by University of Toronto neuroscientist

Dr. Luis Fornazzari has shown that artists and musicians suffering from multi-stroke

vascular dementia can still express art from memory, even when they fail completely

at simple daily tasks and recent event recall.

“Due to their art, the brain is

better protected [against] diseases like Alzheimer’s, vascular dementia and

even stroke.” Fornazzari believes that, “…

the talent and the art per se gives [them] reserve when the brain requires that

reserve.” One of his severely affected dementia patients, Mary Hecht, was a

sculptor. Mary quickly sketched a portrait of cellist Mstislav Rostropovich (below) when she heard of his 2007 death over the radio. While drawing, her thoughts were

clear and her words articulate – otherwise, she couldn’t tell time, remember simple

words or identify certain common animals.

So there is neuroscience

to music.

In artists, it connects brain patterns and reconnects lost memories.

And exposure to music does

rewire neural circuits.

In children, it helps with focus, memory and attention

skills.

There is a secret chord.

“But you really don’t care for music, do you?”

“But you really don’t care for music, do you?”

Although baffling to some, we in the Square still listen, in search of the divine.

No comments:

Post a Comment